- The Logo Edit

- Posts

- The Cost of Expression

The Cost of Expression

Movement said what words could only merely suggest

Welcome to The Logo Edit.

This publication is exclusively supported by its readers. To enjoy future posts like this, consider becoming a paid contributor.

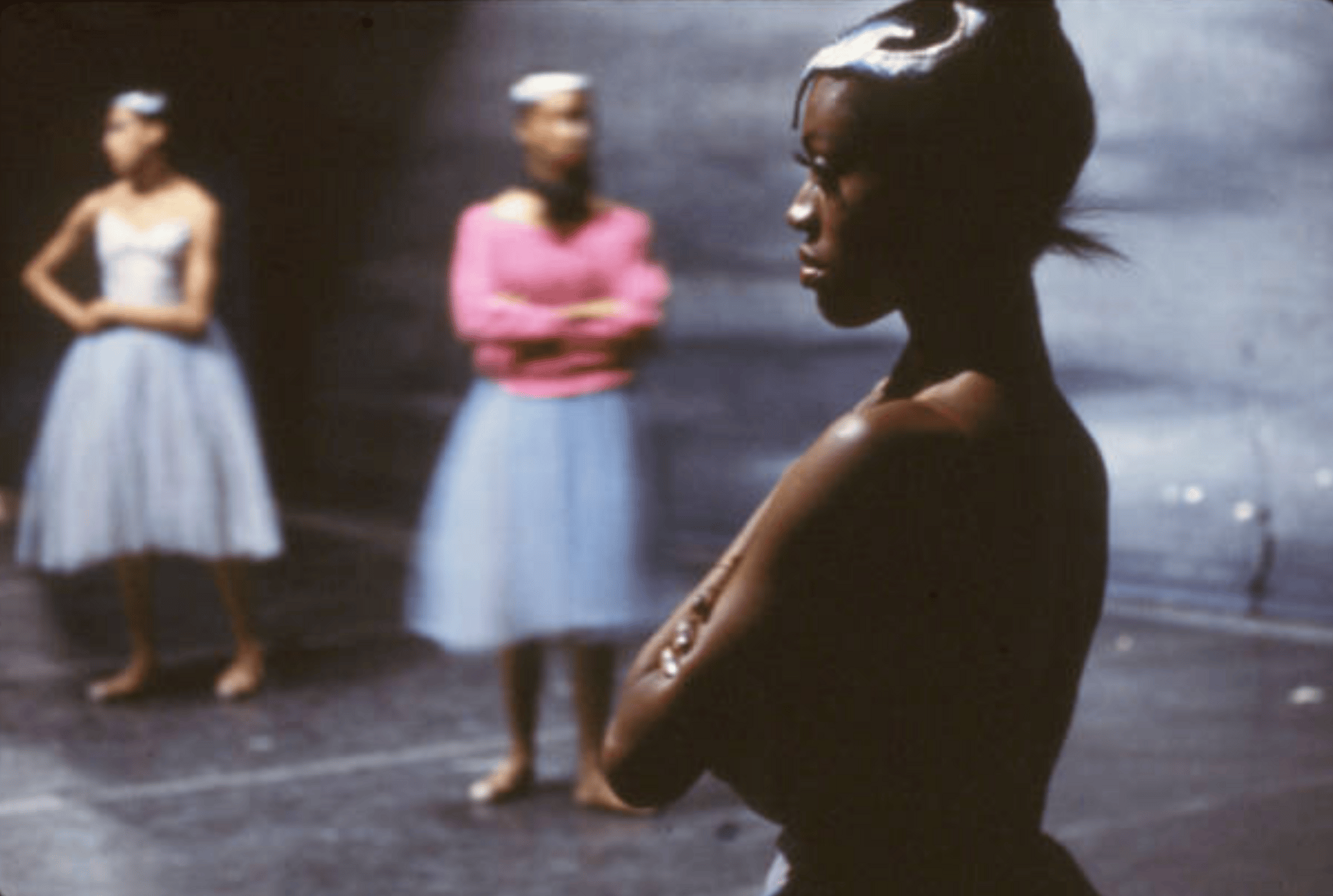

Arne Folkedal, Kimma and Lyman in Diversion of Angels

What was more useful, pouring into the outside, the inside, or the unknown?

In other words, what were we keeping in first place? Half-dormant relationships, self-direction, or dialing in on the ideas we preserved on paper to give to the world?

Control and our understanding of it -by itself- was at the core of how we felt fit to prioritize the pieces of ourselves and our abilities. When presented with what to pick: life or work, we chose what we thought we should handle, what almost felt right. Most people had it all pre-planned, though: what they would cling onto and let slip.

It was said that the individual was capable of either great art or great life, but not both.

Selecting between investing in craft or being often tangled many into indecision since choice was a trance of the murky.

“Grapevines, mango, peaches, and lime, a sweet life…”

“Let me—live out my dreams until my heart give out…”

What we had yet to understand when assessing the good life’s price was the realization of an option’s attachment to surrendering.

Through music, we were able to hear what these two ideals provided. Each portrayed a style of existence away from one another. They also touched on the silent, unseen debt paid in exchange for the other, all while staying under the roof of a vision realized.

If each seemed tangible and inviting, which one ultimately led to a better feeling?

Arne Folkedal, Tina Santos as Japanese Juliet in ‘Shinju’

If we gave up our lives for work, we would be known amongst those who lived, distinguished by what was graciously given. Yet, if we gave up our work for life, what kept us moving with reason?

Because these two words had already come separate, they tended to be spoken of as unlinked. Nonetheless, they felt as though they couldn't be without the other.

I was reading a few weeks back about a dancer who often sabotaged anything that didn’t have to do with her work. As she made her way to being known for her greatness, her surrounding environment caught on to her revolution; they became envious and chatty and frequently commented about her ways; her own madness. She was the topic of discussion and stayed in their mouths.

She had a way about making people comment about her without really knowing much at all. One common theme they attempted to use against her but couldn’t was how she used those, particularly men, around her for the sake of execution. They felt as though they were her props, always ready and just around the way. Her choreography was the accumulation of how she prolonged what she saw as connection. It reflected how she took each moment as not only an opportunity but a step toward lesson stacking and future teaching. As these individuals remained a part of her memory, she demonstrated and multiplied what (to her) were the dimensions of physical and non-verbal pronunciations of expression.

Being disciplined in any field meant that you could one day be celebrated for the space you complemented. To be treasured by many or some, -whether today or yesterday- to some degree, you gave life the permission to use you.

As someone who used their body to articulate the unspoken, she made it clear that to be completely made, you needed to be pliable, eager, and familiar with technique.

Image by Liam Woon: Judy Tyrus; Eddie Shellman

If we were to apply the concept of her life’s practice to business, what could we take with us?

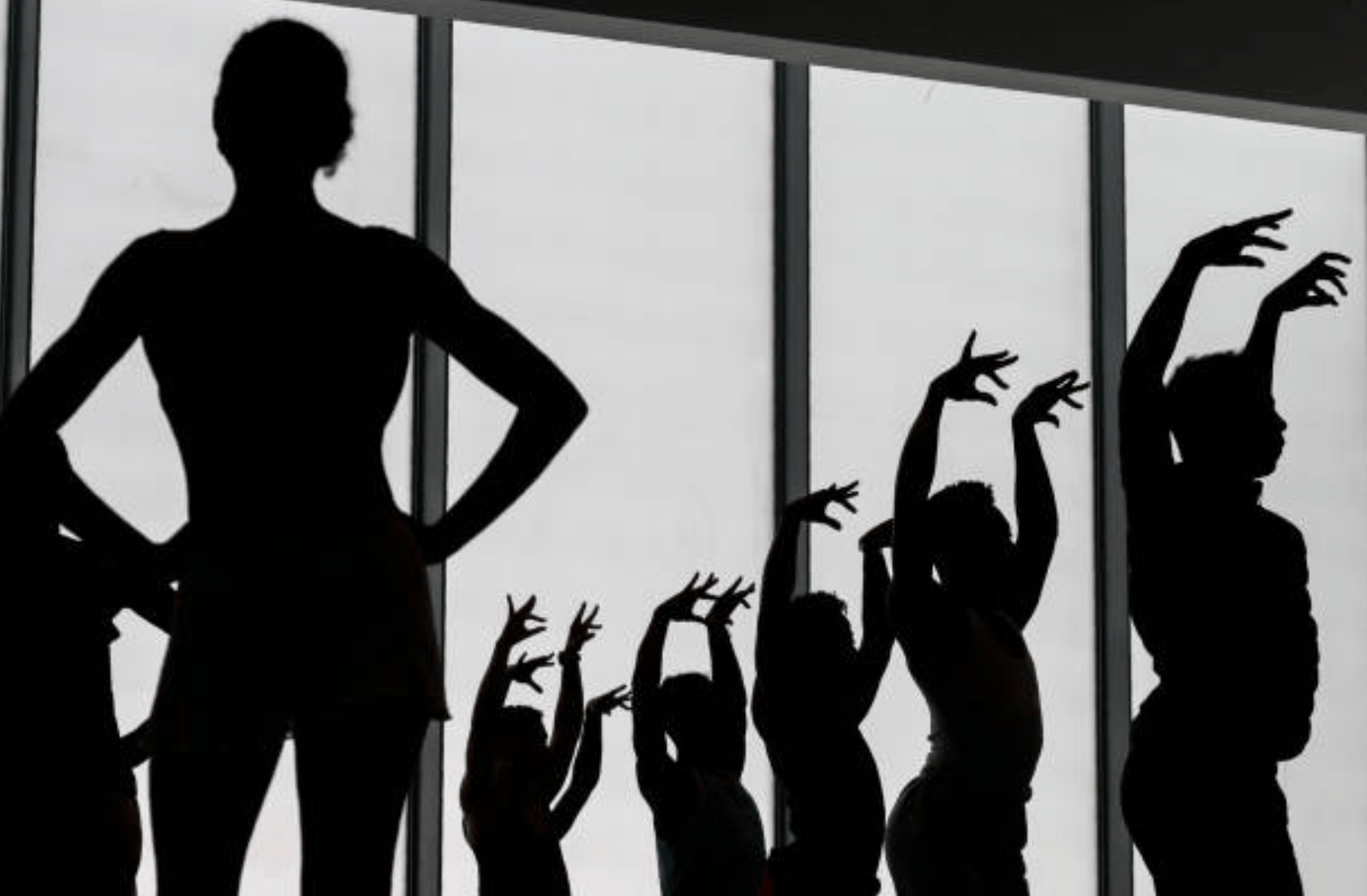

In dance, movement was the reigning constant, unable to depart from truth. There was an appetite for space that the dancer held, looking to make concrete a set of emotions, a collection of testimonies. Those who performed this yearning rarely made it look faint, it was written all over them.

Both dance and business were disciplines partial to being the main attraction; the center of the stage belonged to where they traveled. They had their laundry lists of demands, the order of their wishes. When we want to think about how we engage with the world through our attendance, declarations, style, spirit, and tone, it is essential to go back to the original cause: meeting at the bridge of human experience, the motor that allowed for this gathering.

It is never too common to combine the territory of a ballerina with that of a tycoon, but they trained and carried out their duties with similar intent. Living at the studio, the office, the airport, honored as the artist, the pioneer, the brains, the legend.

They were hardly separated from where they were made a necessity.

Image: Niklaus Strauss, Merce Cunningham Dance Company in Beach Birds, 1991

Here is a collection of observations: some of the ways dance and business merged as one.

Time

Each had a designated lifetime

If you had no hunger to develop, the route to finding yourself would pass you by

As life went on, your purpose changed, too

Our world didn’t always match our memory

Photo by Anthony Barboza, 1983

Routine

Rigor and repetition were what made you change form

You needed your quiet time to let ideas flow to you

Narratives were constantly begun, paused, returned to, and let go of

Keeping track of what you created -building an archive- was just as important as making

Make time to find your support group: isolation does not always equate to comfort

Performing elaborate experiments is the nature of the field

Everyone made their own rules as they moved to the beat of whatever they heard

The nature of the world was easy to come by - it was all you were surrounded with

The fear of the unrecognizable was like a cold everyone got at some point that eventually went away

Photo by Afro American Newspapers, 1965

Impact

Each discipline had an acquired taste - visible and not

Having some talent got you into some doors

Even if you occupied a certain domain, it was never that easily defined

When engaged, it felt like you were filling a missing piece

You had to use your own eyes and thinking to conclude, change, and question

Your influence could be directly/indirectly coordinated with culture, thus affecting what the center of your universe was

Your work was also an attempt to embody the fleeting, remaining, and steady concepts you had in your head

If you can turn something complex into something comprehensible, you’re getting somewhere

Photo by Anthony Barboza, 1983

Mindset

Some get into each specialty subconsciously, craving a type of consistency, protection, and safety in their life

Being “right” was nuanced and nonlinear

Discipline has to be fed to you in a way you understand for you to want to follow it

Maintaining a narrow point of view doesn’t get you anywhere - it only gets you a quarter of the way to where you’re trying to go, at a much slower pace

It’s not unique to want to give up and quit

Your path is what you envision for yourself, and it's made from what you think it can be

Comments and criticism were overcome with resourcefulness, inspiration, and purpose

Keeping the theoretical channel of receiving open was central to your practice

Vault mentality was key, being output-driven and having big-picture thinking - the work had to be left in someone else’s hands someday: whether you knew the date or not, this was reality

Photo by Santi Visalli, 1987

Reminders

You were in the position to be chosen by your mission; you just had to take it

“Failing” and recovering were just as common as breathing

Debating if the work was good and valuable enough + making general comparisons to no end, was not useful

Your start never dictated your finale

Each day, you were delivering a certain level of physical ability that reflected something else in you

Being focused on the overall composition was crucial: with no material, nothing existed - there was a need for a set of components to be deemed complete

There was something about the first feeling in creation - no matter how many other iterations were made, the beginning, the initial idea, could never be pushed to the side, neglected, or lost

Photo by Anthony Barboza, 1983

Becoming

Whatever you did in each environment helped you approach everything else in life: ie, having empathy

You didn’t need to be born a prodigy to have a chance

You’ll never be in the same place twice

Reaching mind-blowing status meant embracing your epiphanies, whatever you held in the dark

What you want for yourself is ultimately bigger than you are

Every calling requires absolute devotion

Your gifts were your responsibilities

People alternated between being still and full

Photo by Anthony Barboza, 1983

From tradition to mastery, permanence to the unlasting, etiquette to form…

Photo by Andrew Caballero-Reynolds, 2019

The intricacies of each practice were found in the non-verbal, the details of attention.

Photo by Anthony Barboza, 1983

For more real-world application + support on how to use research to better communicate your ideas and projects, send us an email with what you’re building and we’ll get back to you within 24 hours.

See you soon

~

Madison

Reply