- The Logo Edit

- Posts

- Nowhere Else But Here

Nowhere Else But Here

Breaking bread with intimacy

Welcome to The Logo Edit.

This publication is exclusively supported by its readers. To enjoy future posts like this, consider becoming a paid contributor.

Susur: A Culinary Life, 2005

cooking | ˈko͝okiNG

noun

giving • owning • using: involving oneself with the temporary and supposed enduring.

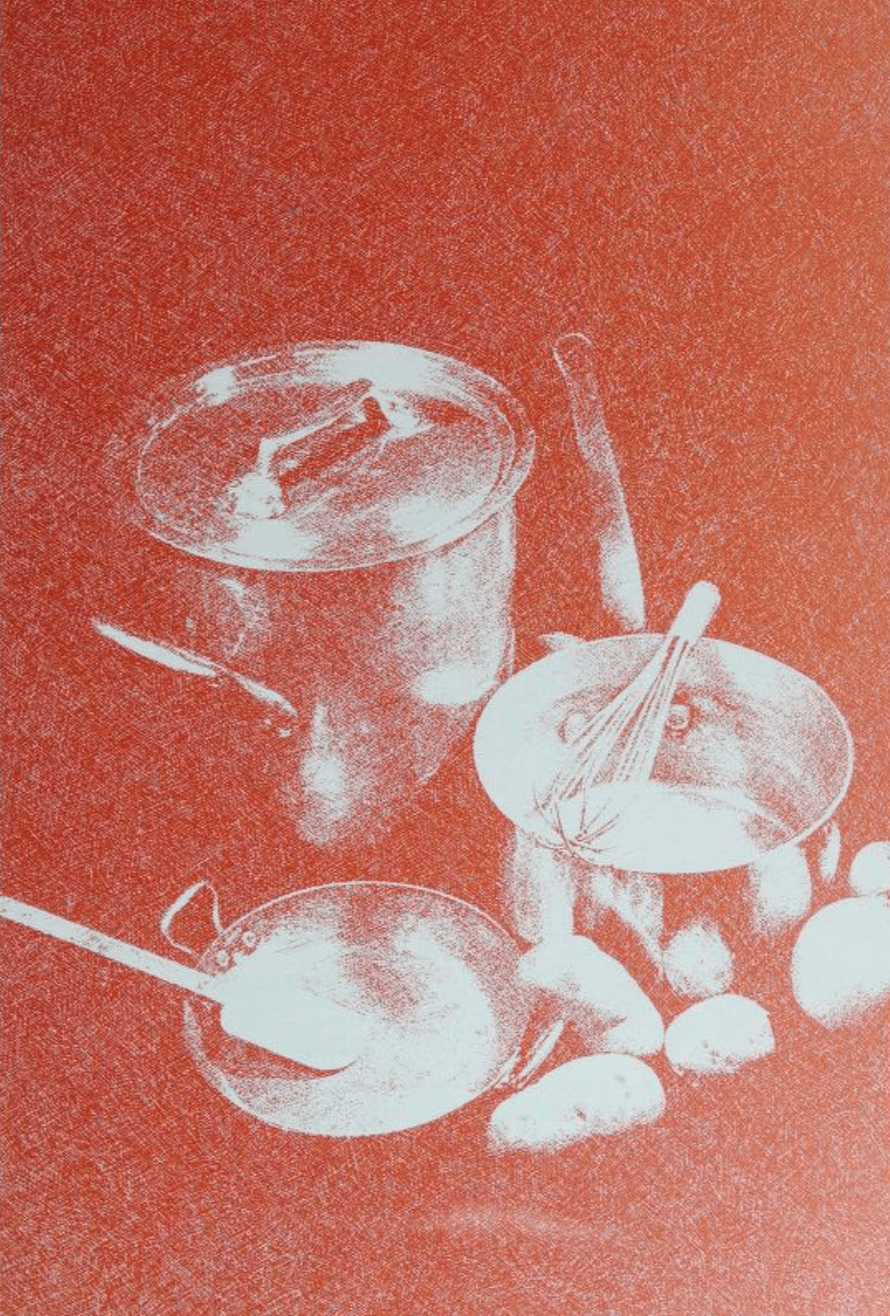

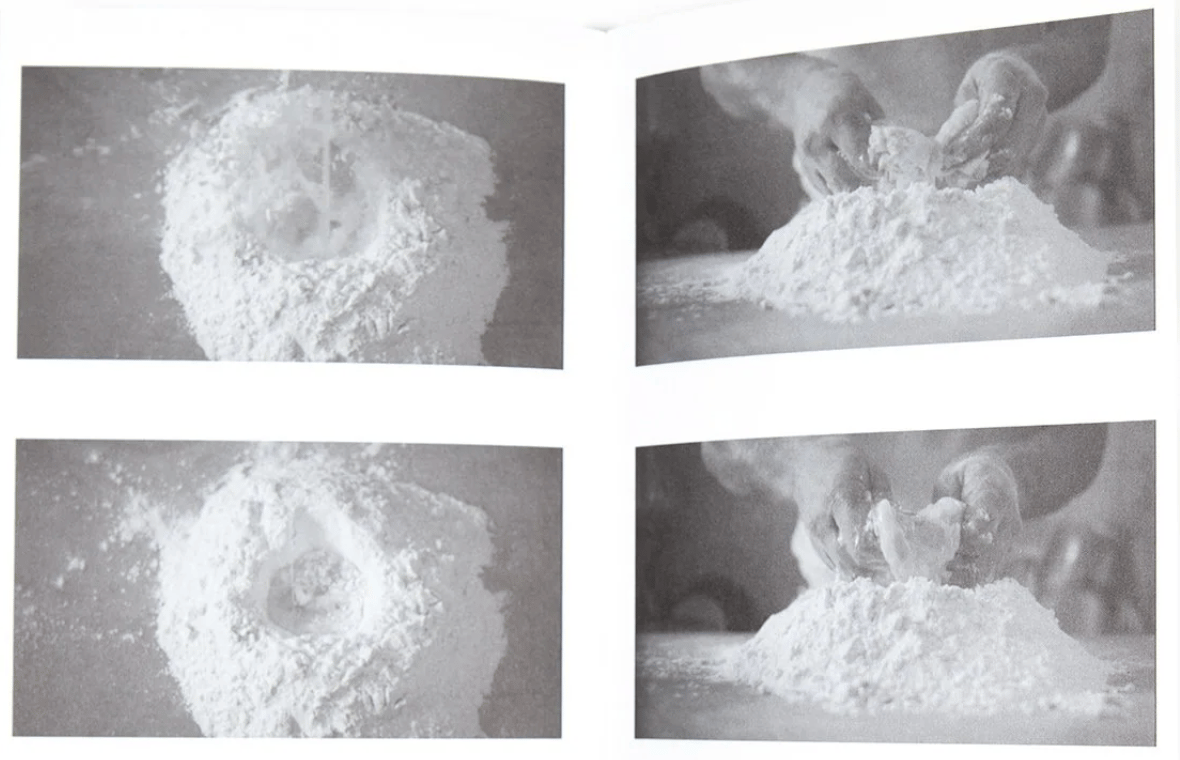

From Julia Child's Kitchen, 1975

From Julia Child's Kitchen, 1975

As they were, there was a shape that resembled a psychological union: table and meal.

When we think about eating, we have a pool of references to choose from. Alone, in company, in memory...

The relationships we formed at the place we nourished and contributed to was a. communion of layered pleasures.

Recreating “pleasure” was something pronounced and designated. There was a texture to it, a succession of bonds and surprises. Its construction seemed like it only came around when our hands were off the planning train, when we just let the next event proceed the present.

The language that captured us in pleasure was what it was consciously grounded in by definition: fulfillment.

Just as in the intimacy of cooking or starting something new, re-attempting made us crave accessing the depths of delight.

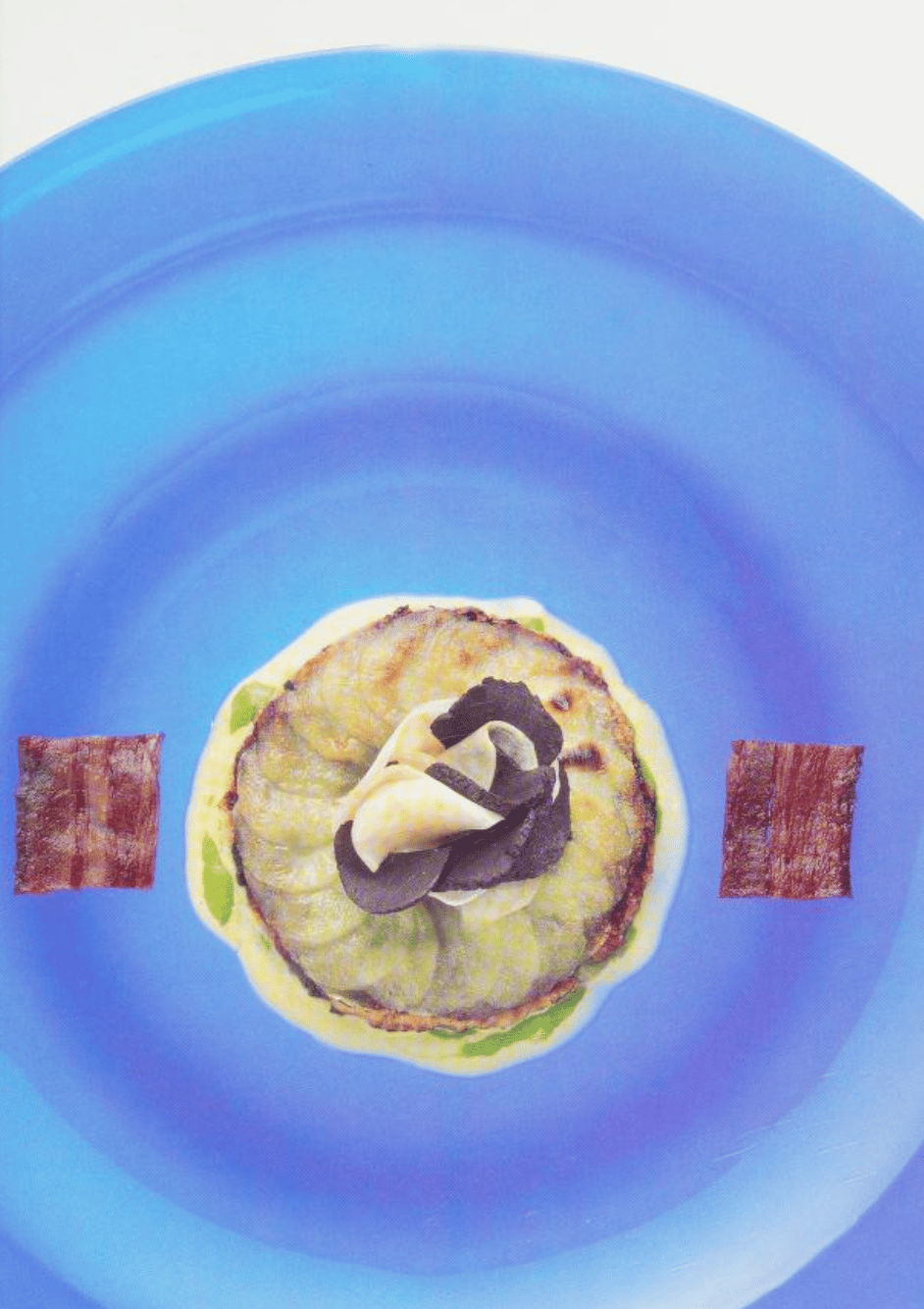

Susur, A Culinary Life, 2005

The kitchen was where you got a sense of what you were good at. It was where the palette was brought to light, where you familiarized yourself with giving. When you took into account what to communicate through food, what to distribute, share, and leave for later, you began to visualize the ones to eventually eat with you. You pondered what they would remember, enjoy, and savor, not just ingest politely.

There was a space reserved for considering in cooking: choosing what would be needful for the body. There was an interest in interfering with what it could handle: what was to be deemed heartful, special, unfading.

Cooking gave you the hand to withhold and serve what was good, whenever you felt this was due.

Preparation, reservation, plating, and serving were examples of ultimate tests that showed you how to learn your own liking, become warm and filled on an individual level, practice until you were incapable of forgetting, and, when least expected, recreate what you just realized for someone else.

Beyond the kitchen as a place and what it represented, cooks and the actual art of the discipline had you jump from phase to phase to register what you wanted to revel in for a while. You were to go from idea to inspiration, recipe to feedback, serving to experience, moment to memory.

Susur, A Culinary Life, 2005

The first realm a cook entered was something along the lines of an alimentary awakening. You either had a picture already painted, or you got into what I called diligent muse searching. You let yourself find and allowed your diary to take shape. This type of “capturing” went going past staying in place. You moved because you had yet to arrive at what was material.

In the midst of this unfolding, you most likely started (physically) near your native shores, the region you knew like nothing else. Later, you would mentally drift, granting an ingredient’s ability to find you. This gesture, this course, was insistently personal. You were touring your own mind, sorting out hazy reminders of a checkered past: investments in illusions that were considered prior to what you recognized today as comforted relief: meals and the company you kept.

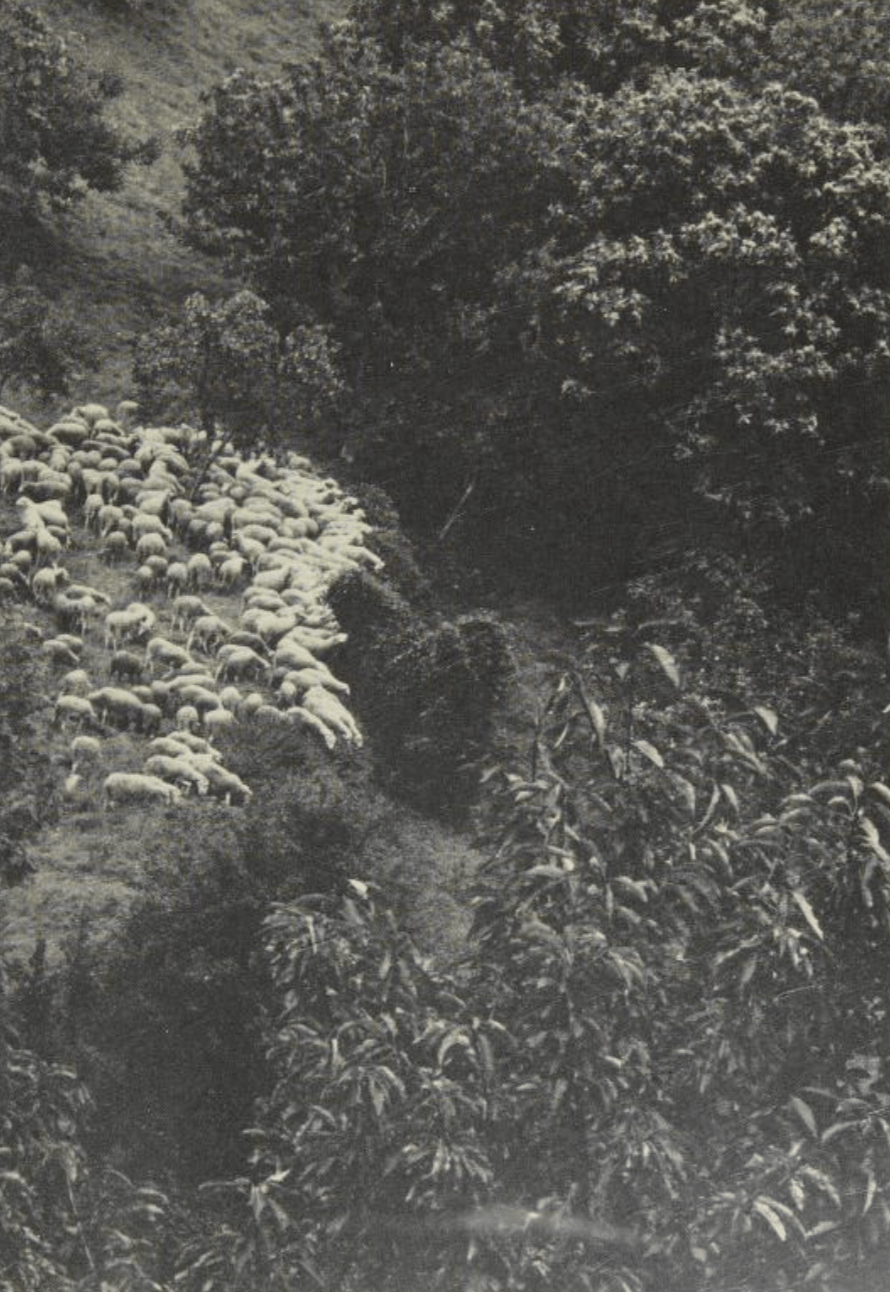

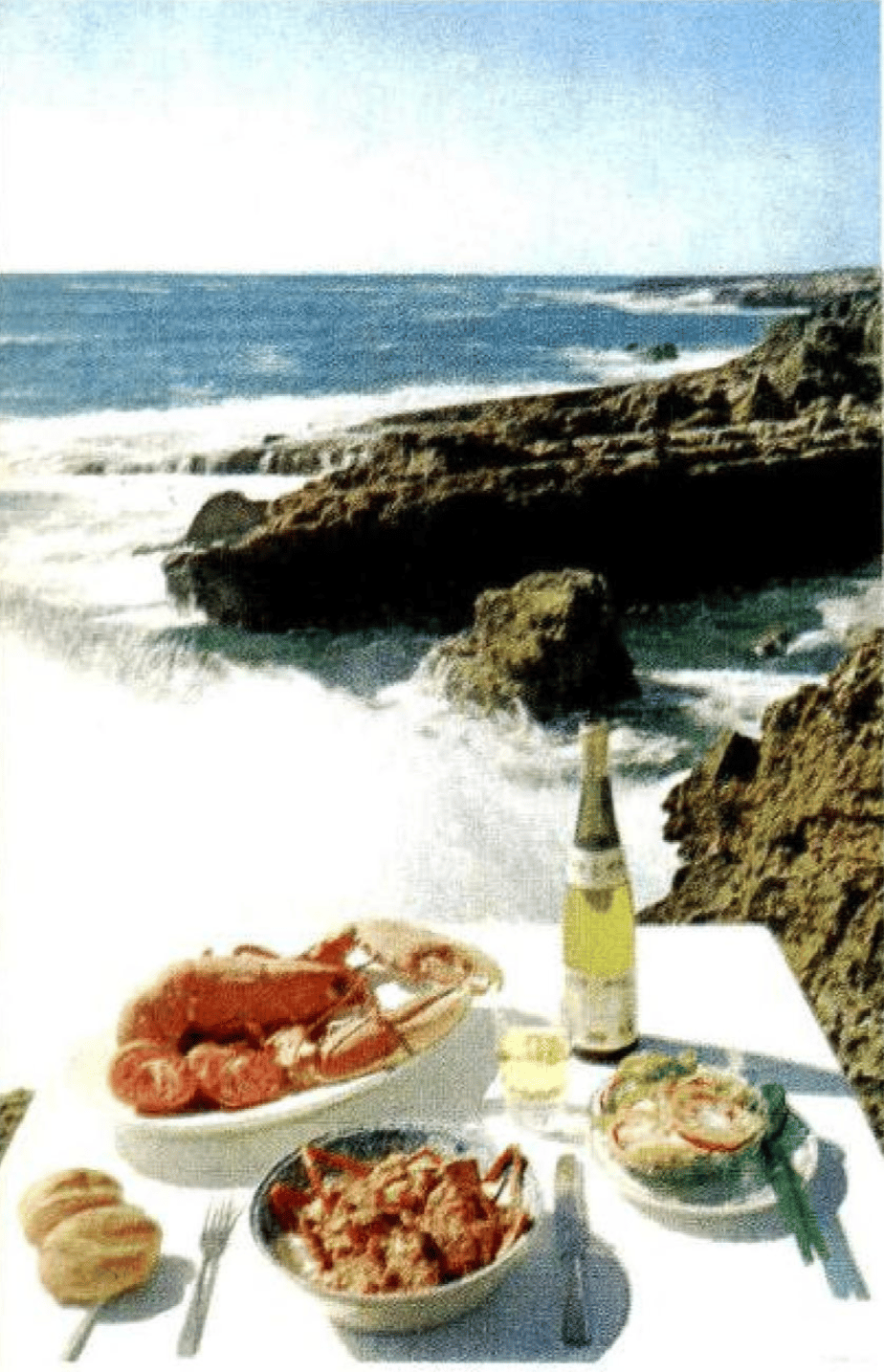

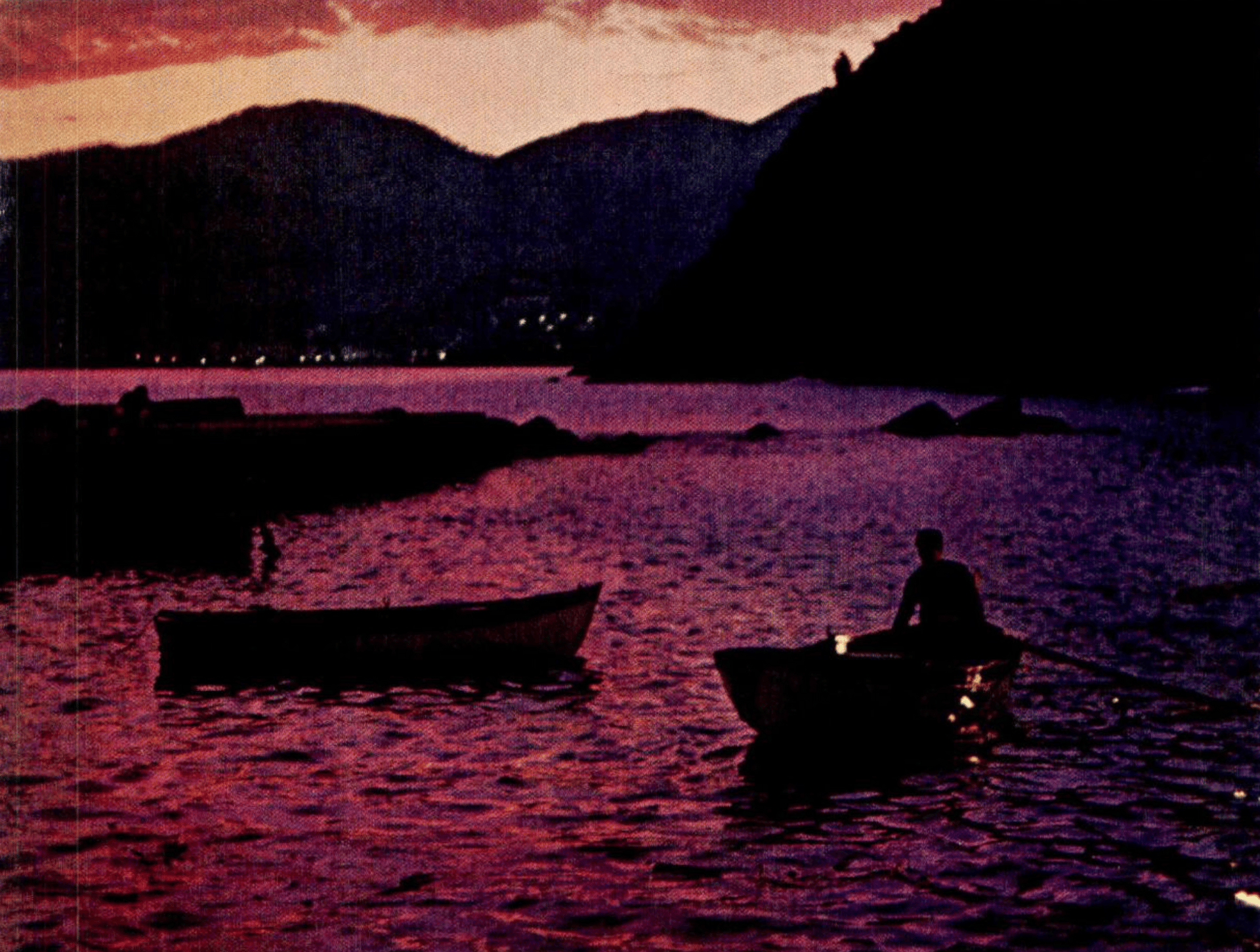

Peter S. Feibleman, Cooking of Spain and Portugal, 1969

Finding what to make lied in keen observer-ship. It required a tolerance and compassion that was total. When you tried your hand at your own romance with ideas and vanished eras, you collected information for the self that was plenty. The habit of this and that looking was a reference muscle, knowing (well) the things we tended to want to see all the time. This was the before of putting everything away to just start cooking. This initial step exhibited the room that existed for a great renewal: revisiting autumn afternoons, summer nights, spring conversations, winter lessons. Looking into these distances and their inner workings unbuttoned the stage that was revelation.

Waverley Root, The Cooking of Italy, 1968

Proceeding the impulses of invention, came the forces of posture at play: cooking with both the ears and the eyes, reading into the depth of the senses. Like the tools we knew to call pots, skillets, and pans - some were quick to heat, and others slow to cool. When we sparked fuses from afar, we connected the use of our hands to activate the brain. The progression that became food-to-bowl was captivation to initiation: observation, escape, and their cooperative development.

Being impatient to just have what you wished to taste, meant that out there: where you were searching, didn’t show you what you wanted to find.

This compelled you to compose and produce, to carve out the living.

While almost all is subject to gravity, you filled your heart and head with labor, making use of your whole being to depict a sensory impression, not trying to overdo / overwork / overthink.

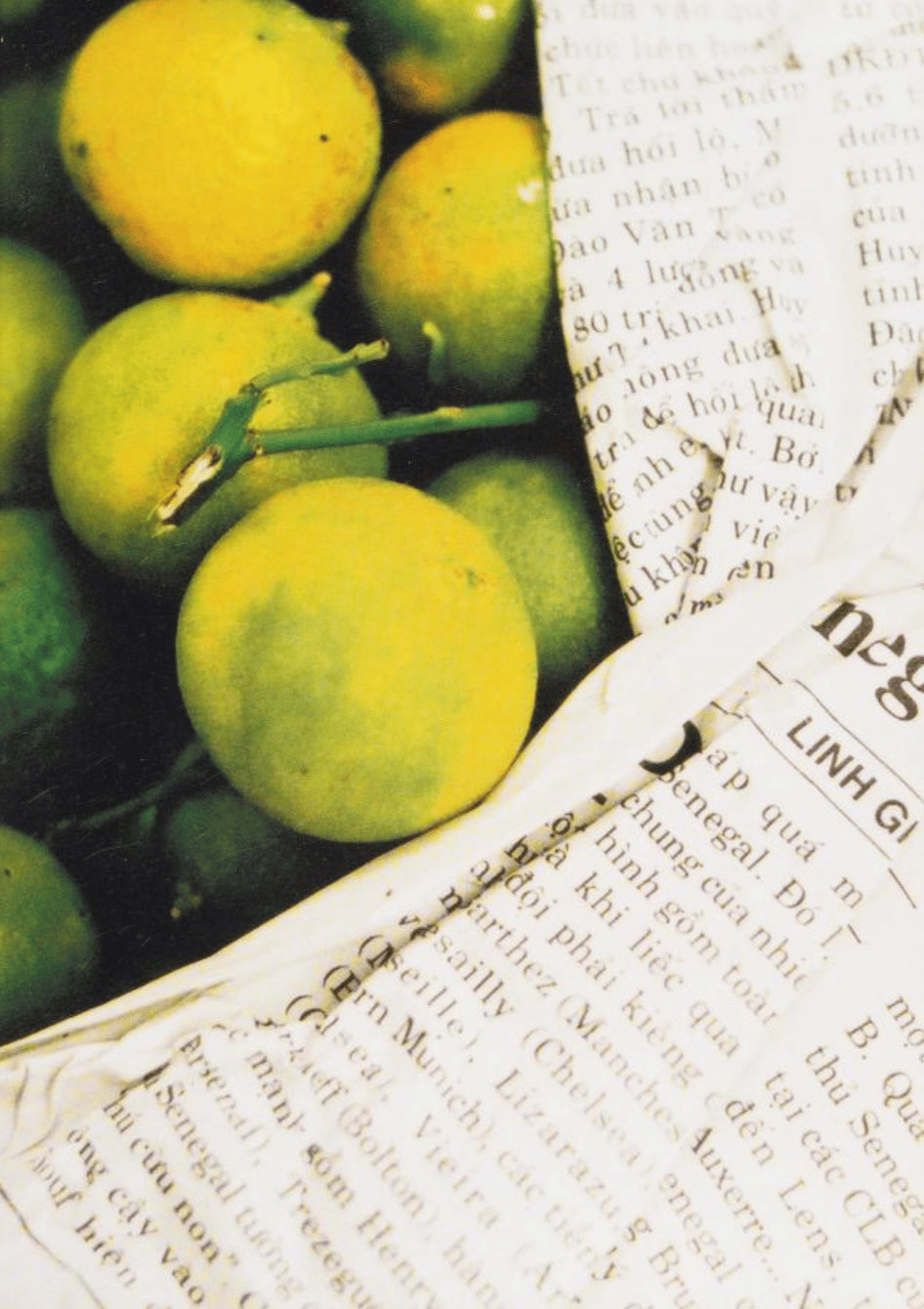

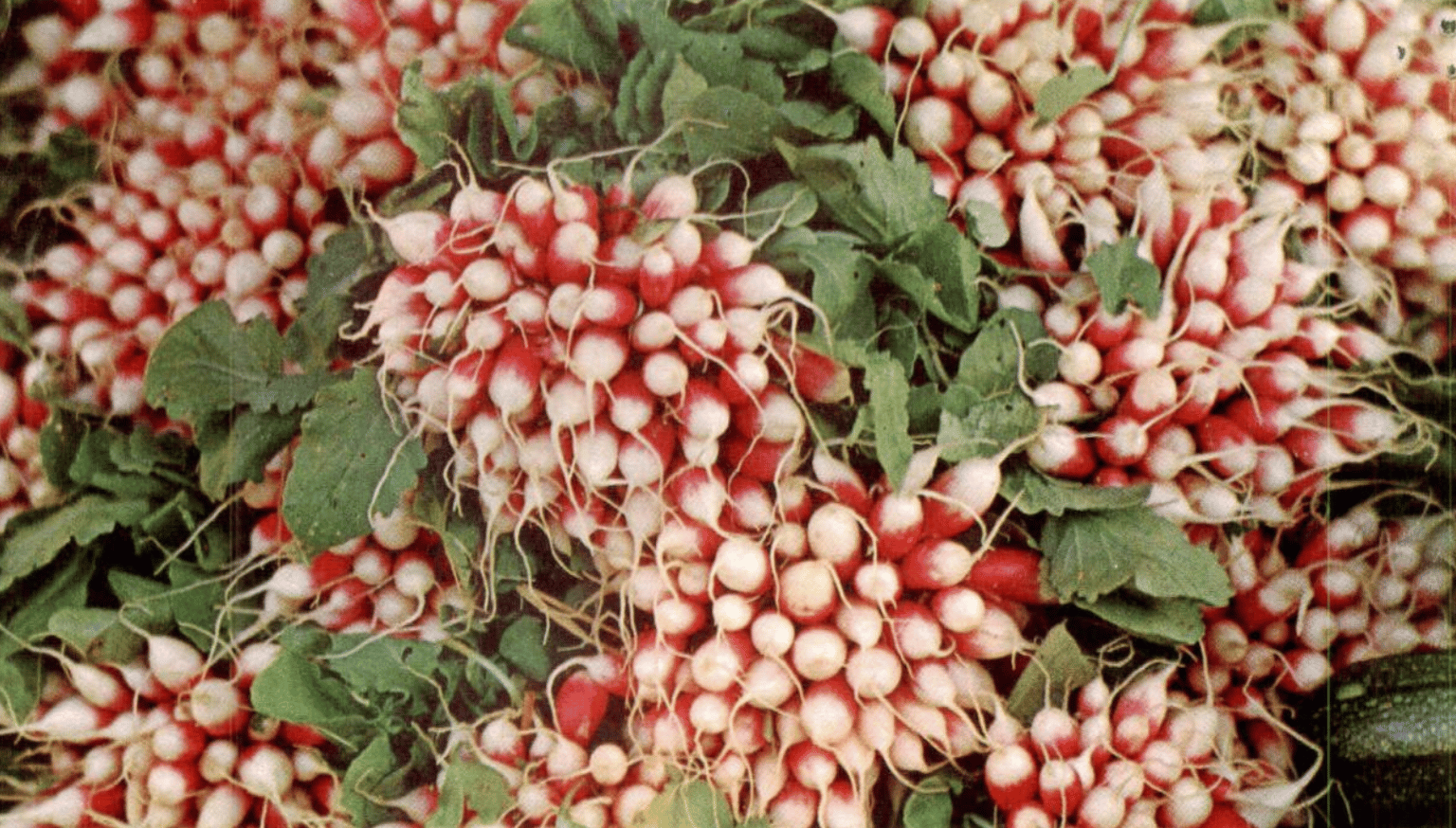

Sally Anne Scott, Versatile Vegetables and Salads, 1992

Figuring it out -this robust doing- was unfashionable to the outside, unfavorable, and disorderly. Consuming, tossing, and remixing made vivid your plans and aims. Excitement would spur, and hesitation would ensue as you shattered your own predictions and became unafraid: when you asked questions about revisiting ground zero, you re-measured what you did once deliberately. Starting back at one, uncomplicating the complicated was mostly forgiving since you were reassessing your relationship with substantiality or otherwise known as fate’s seasons: harvest and proportion, land and soil: enunciating your version of craft and ritual.

This was the silent calculation (on your part) of excellence, exceptionality, and extraordinariness. It was the coveting of preciseness and delicacy, intensifying the polarities of taste and their extremities: salting, spicing, sweetening, acidifying, making bitter...

Giving in to wondering which ingredient was distracting from the feel of the overall bite, which was too pungent, muted, raw, tasteless, or overdone, was a part of examining, valuing. Laying out the significance of the insignificant, working your way to making changes led to windows of alternating, never remaining too fixed on one thing.

The Creative Cook, 1996

Meditating and ruminating on the final product resulted a lot in determining what you saw as the right way to do things: throwing yourself into your irresistible instincts, taking part in the internal, hearing, listening, and competing with composure.

While you cooked, you occupied yourself with height: seasoning from whatever the in between of high and low was so you could see what you were doing: simmering, distilling, creaming, filtering, lifting, removing, whisking, basting, saucing, assembling, decorating, garnishing…

Being patient was not about seeing what was easy to make. It was about getting rid of the most difficult steps right away, anticipating how to eliminate catastrophe and unnecessary losses.

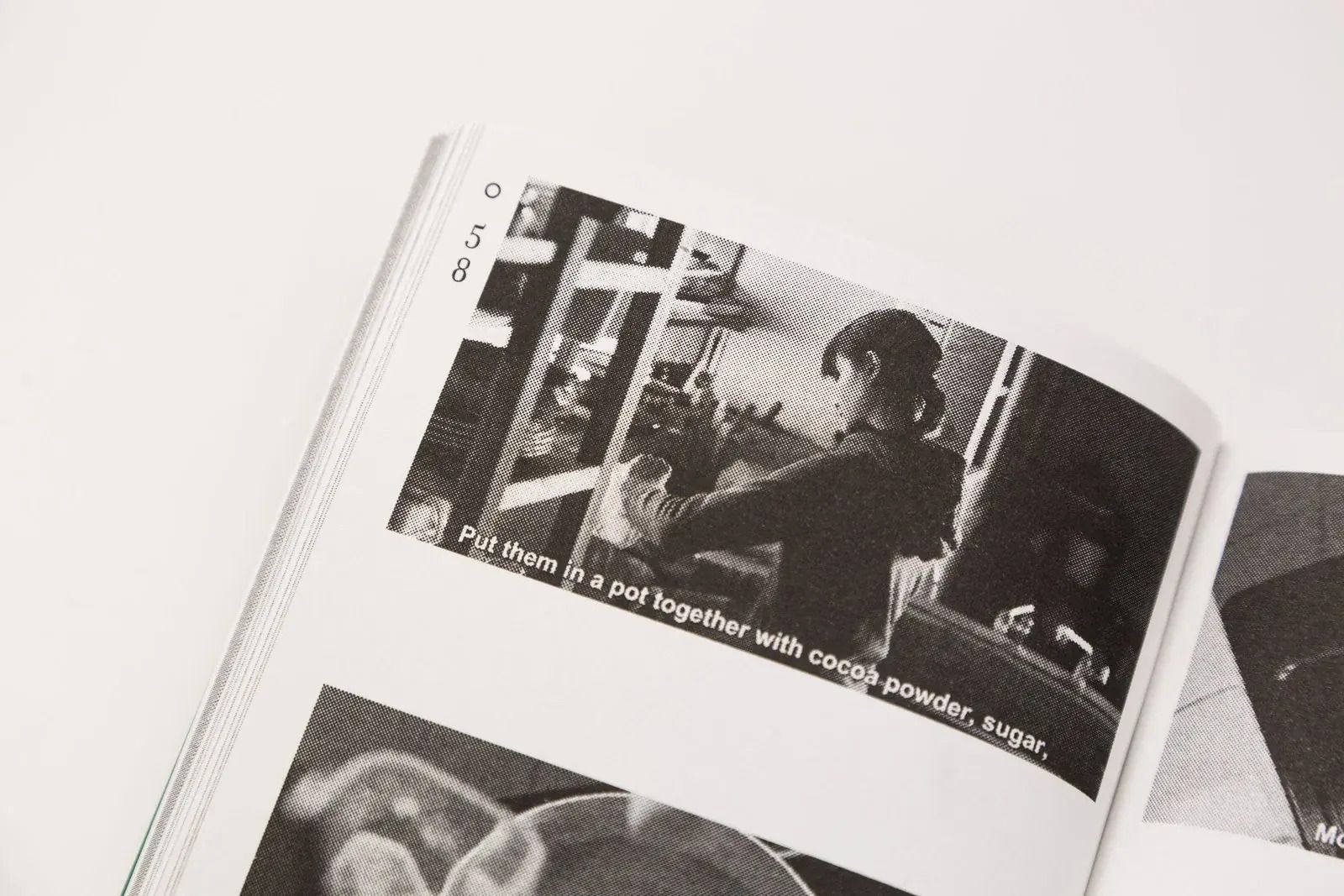

Cooking with Scorsese and Others: Volume 3, 2019

Counting all of the bones made you think of a certain something. Collection and development were other words for counseling: what you needed to confirm that your food was not just edible, but reasonable, beneficial. When you cooked, you always reached a point where there were no names to compare what you made to anything; you were just left with the shapes of your own creation.

Here is where stamina involved itself, signaling what exactly should be eaten, plus when, how, why, and where, with the help of another’s interpretation. When you asked about what you did, you caught on to people’s understanding of minimalism, maximalism: you became privy to what they determined and how many spoonfuls it took to reach a conclusion: whatever they saw as sublime and ridiculous, you were faced with looking into their now.

Peter S. Feibleman, Cooking of Spain and Portugal, 1969

It took a city to know when to stop, detour, and know what was worth the special journey. Live and active responses forever changed the equation, the clock to your recipe. Asking for help took you a long way. It prevented stale reactions and showed you which paths were worth breaking. This was the phase that got you from “try this” to “it’s working”.

Cooking with Scorsese: Volume 1, 2014

Even after you inquired about the heat, you still wanted to check it. Radically embracing a meal meant catering to the moment it would hold, keeping what corresponded to nature alive.

Making it all up from here after toying with fragrance and taste, enduring and feeding opinion and critique, made judgment morph into concluding: thinking about what you wanted to do even after all of the portion checking, correction, withholding, sparing, election, and addition.

This public display of a set of trials and serving on repeat until you got it just right was where you initiated the preview of reception. Here, you could stir up the courage to do something different with the time you had left or keep the good thing the good thing: weighing and taking out what could be done next and better. You verified how far you wanted to go, learning from replacement, tragedy, reversion, resistance, and dysfunction: differentiating flavor and practicality.

M.F. K. Fisher, Cuisine de France, 1971

When you were poured out like water, all you felt was repetition: an over again. When you recuperated the markings of a particular essence produced, there was no staging left, no falsities to combine. After you stopped stirring, what you disclosed was an interruption from the lush present, an appetite for the sole now. The more you drifted from curating, the closer you got to evoking and reaching the prose of a meal: its reputation and merit.

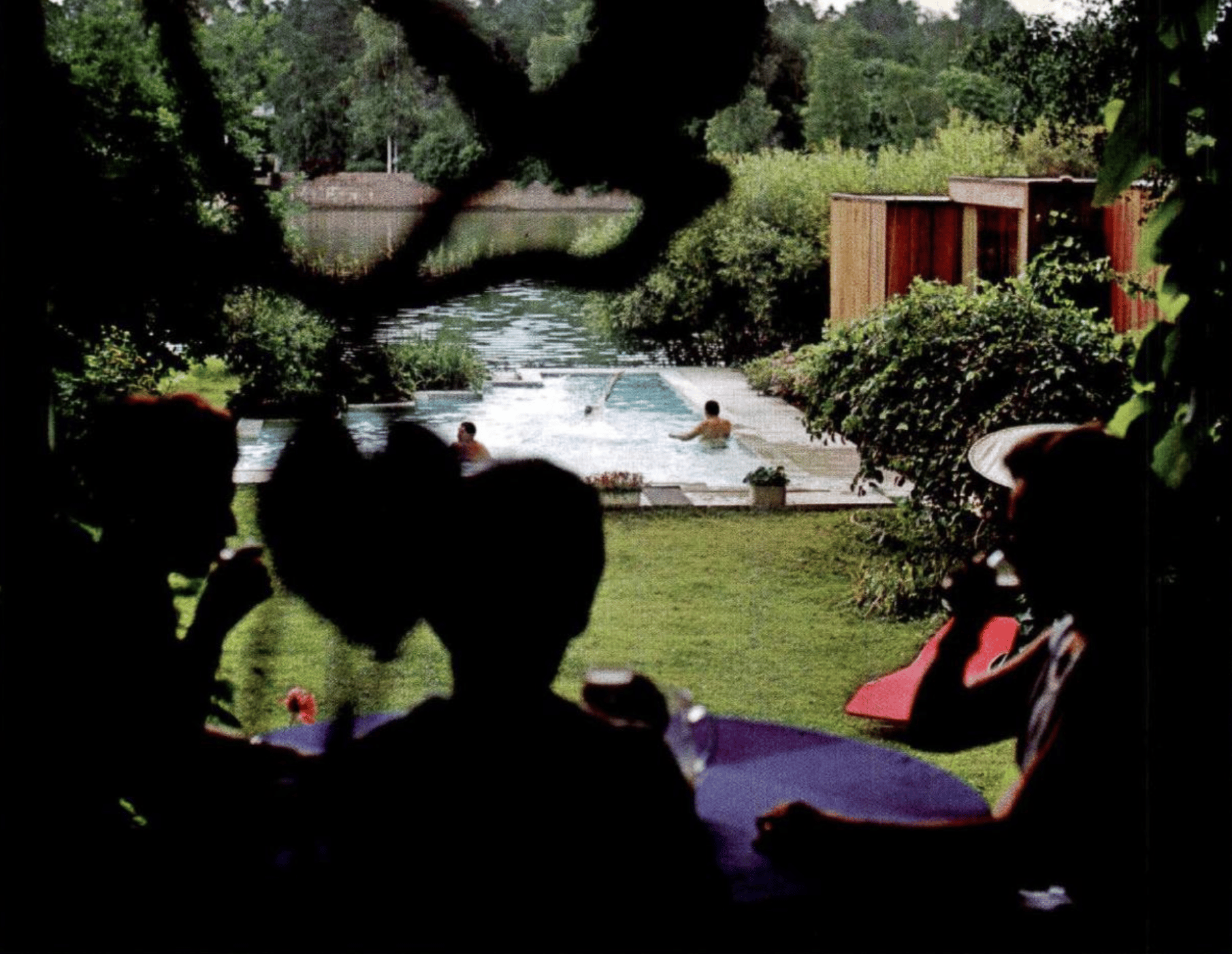

Dale Brown, The Cooking of Scandinavia & Recipes, 1974

Whatever you presented as is, was your arrangement: sink or swim. This was the culmination of the graciously and ornamentally intricate, insistent: the unconstrained. A moment was made steady through imitated tradition. It demonstrated an echoing of unraveling: sequencing script and action. Living together in concert with your cooking and those who joined, tied to a union of confessions.

Meals were not about presentation or who finished last. They instead taught you how to lean your way into getting to know the ephemeral spectacular. When you pulled the plug on experimentation, you moved into experience. When the food was ready, the surface of sustenance opened. This finite period that was eating, somehow, always lasted longer than predicted, even after forks were no longer in use. It was where the mixing and mingling, the sharing and noticing, led to another form of rewriting a collective fortune.

Mary Slater, Caribbean Cooking, 1984

Aching for a past... The last one to put the lights out knew that they resembled the night being complete. Leaving the kitchen was the comprehension of the closing in on an inextricably circular aftertaste that reached to recount the idyll, the crossroads of joy.

When you turned your attention toward the foods you mapped out, took apart, and unified, you satisfied a singular type of hunger, made for one moment.

A cook often recognized their influence but never trusted themselves entirely. This seldom reliance was not linked to low self-esteem, yet the recognition of emphasis, revealing what remained unnoticed, putting their touch on what was already there.

Adrian Bailey, The Cooking of the British Isles, 1969

Endless reward and contentment came from bountiful discovery. Reminiscing, tasting to remember the unforgettable, acknowledging the hypnotic replay of the novel lives remade through the table that is our memory, made us more reliant on what was here, what was real.

Dale Brown, The Cooking of Scandinavia & Recipes, 1974

The teachings of a moment’s impression was found in what we needed to be essential, recalling the irreplaceability of what kept us: breaking bread with the intimate.

Animating our existence came from what took anything from something to nothing… time…

Waverley Root, The Cooking of Italy, 1968

Thank you for making it to the end of this edition and being a part of The Logo Edit.

For more guidance on how to integrate research into your personal projects, let me know what questions keep coming up as you’ve been building/learning.

See you next week

~

Madison

Reply